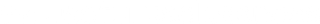

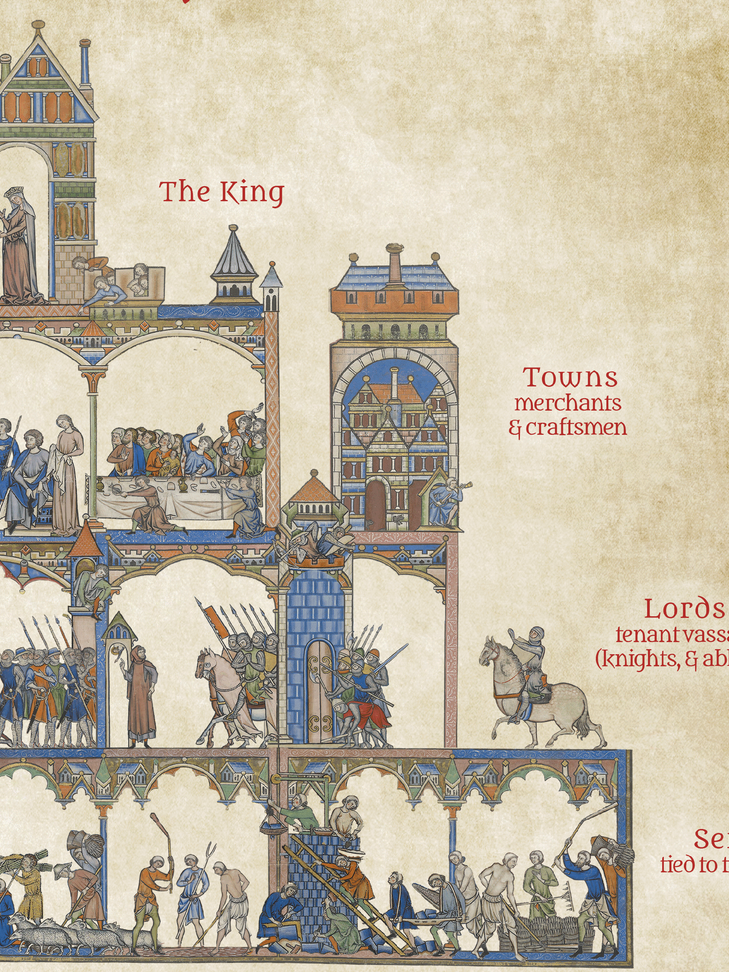

History reveals, with embarrassing frequency, how little we’ve evolved in certain dimensions of collective life. Consider the feudal systems that dominated multiple civilizations across centuries: from medieval Europe to shogunate Japan, from imperial China to the India of rajas. In all these contexts, we find rigid pyramidal structures where power, privileges, and resources flow from top to bottom. At the apex, a sovereign whose authority was often sustained by supposed divine legitimation—or at minimum, hereditary inheritance—distributed lands and titles to loyal nobles. These, in turn, guaranteed protection and sustenance to the serfs who worked the land, extracting from them the fruits of their labor. Social mobility was practically nonexistent; you were born a peasant, you died a peasant—save rare exceptions that only confirmed the rule, feeding tales of heroes and extraordinary figures that generated hope which, more often than not, proved unfounded.

Now, step into any office building. On the top floor, spacious offices with privileged views house the “C-suite”: CEO, CFO, COO—our new corporate royalty. On intermediate floors, directors and department managers—the dukes and counts of our time. On lower floors or in open spaces, we find the “collaborators”—the new serfs of the digital manor. You might say: “But this is an exaggerated comparison! Today we have meritocracy; anyone can climb the hierarchy with effort and talent.”

Is it really so? Have entrepreneurial success stories become the new “heroic tales” with entrepreneurs as protagonists? Have materialism, capitalism, and consumerism replaced religion as belief systems that sustain and justify the established social order?

power structures: more similar than they appear

Just as feudal power justified itself through supposed divine right and evident genetic transmission, contemporary corporate power legitimizes itself through a quasi-religion: the meritocratic ideology of late capitalism. The medieval sacred has transformed into the mercantile sacred. The new “divine right” is now conferred by MBAs from elite schools, by privileged contact networks, and by an esoteric language of “leadership competencies” that few master and even fewer question.1

The feudal system depended on elaborate rituals to reinforce social hierarchies: the ceremony of vassalage, tournaments, court banquets. Contemporary organizations are no different. Think of annual meetings where senior management presents “the strategic vision” before a reverent audience; exclusive leadership retreats for top management; team-building events that, under the pretense of building teams, subtly reinforce who’s in command and who must obey. These supposedly playful and egalitarian activities in the workplace often serve to reinforce hierarchies and perpetuate infantilizing dynamics.

Modern examples of this caste mentality abound. Until recently (as of early 2025), some well-known companies maintained an executive-only elevator—a physical manifestation of hierarchical separation reminiscent of differentiated entrances and accesses in feudal palaces. These practices, far from being anomalies, represent the materialization of a logic that permeates organizational fabric.

I remember working with a team whose director consistently scheduled meetings for late Friday afternoons and evenings, using loyalty arguments to keep people present despite acknowledging the personal and family constraints such behavior caused. Similar patterns repeat between large companies and small suppliers: proposals, reports, and other elements requested for Monday, with Friday as the deadline. Curiously—or not—many responses from these same clients took weeks, months, or never arrived. The “feudal lord” summons, the “vassals” rush. And just as in the Middle Ages, vassals feel—or are made to feel—privileged to be summoned by their lord.2

bullshit jobs as modern servile labor

David Graeber identifies a peculiar category of the modern economy: bullshit jobs—positions that even their occupants secretly recognize as unnecessary or even harmful to society.3 Graeber notes that many of these roles exist only to satisfy administrative whims or maintain the appearance of productive activity.

Paul Tabori, in his work “The Natural History of Stupidity,” offers a complementary perspective. According to him, bureaucratic stupidity is not accidental but structural. It’s the inevitable result of hierarchical systems where obedience surpasses intelligence as the primary virtue.4 Any similarity to the corporate world is no mere coincidence.

This stupidity manifests in various forms. Observe, for instance, the endless layers of approval required for trivial decisions. Or consider the detailed weekly reports that no one actually reads but everyone must produce religiously. The periodic meetings where most participants shop online, update social media, or “dispatch” work they can’t complete because they spend most of their day in similar meetings. These practices resemble feudal tributes—not for their intrinsic value, but as ritualized demonstrations of subordination.

The proliferation of positions with pompous titles like “Senior Digital Transformation Strategy Specialist” or “Associate Vice President of Customer Experience” is another symptom of this corporate feudalism. Looking at traditional noble hierarchy, we find a meticulously detailed scale: squire, knight, baronet, baron, viscount, count, marquis, duke, prince, and their multiple variations like grand duke or count-duke. This gradation served primarily to establish social position, not to describe concrete functions—exactly like contemporary corporate titles.

The correspondence is remarkable. The “Chief Executive Officer” echoes the monarch; the various “Chief Officers” (CFO, COO, CTO) resemble princes of the blood; “Senior Vice Presidents” are modern dukes; “Vice Presidents” the marquises; “Senior Directors” and “Directors” occupy positions equivalent to counts and viscounts; “Senior Managers” and “Managers” are the new barons; “Team Leaders” are knights; and “Associates” or “Specialists” represent corporate squires—all competing for promotions that allow them to climb the office’s aristocratic hierarchy.

The obsession with these titles isn’t frivolous—it’s structural. As David Graeber noted, titles become part of an elaborate status game where what matters isn’t what you do, but how you’re perceived in the invisible but omnipresent hierarchy. “Bullshit jobs proliferate today in large part because of the peculiar nature of managerial feudalism that has come to dominate wealthy economies,” he wrote—a phrase that could serve as the epigraph for our entire contemporary workplace.5

false meritocracy: aristocracy by another name

One of modern capitalism’s ideological pillars is the notion of meritocracy—the idea that anyone can ascend the social hierarchy through merit, hard work, and talent. This narrative is comforting, as it presents inequality as just and deserved. However, it hides an inconvenient truth: social mobility in companies resembles much more the occasional exception that allowed an extraordinary plebeian to ascend in medieval nobility than a system truly based on merit.

In this context of false meritocracy, it’s impossible not to notice how certain Human Resources departments have abandoned their potential transformative role to become administrators of the feudal status quo. The paradox is evident: although Dave Ulrich proposed over 25 years ago (in 1998) a “new mandate for HR” as strategic defenders of human capital,6 many of these departments have transformed into zealous guardians of established hierarchy. How often do we hear phrases like “that won’t work for our people” or “it’s better to have the answer prepared, because people here are very quiet”? This paternalistic presumption of knowing what’s best for others doesn’t differ fundamentally from the logic that justified feudal servitude.7 In the desperate search for strategic relevance and recognition within existing power structures, many HR departments end up betraying their fundamental purpose, becoming active accomplices in perpetuating inequalities they should combat.

Corporate ascension frequently depends on factors that have little to do with competence or productivity: attending the right school, having the appropriate accent, belonging to the correct social (not digital) networks. When a CEO states they seek people who “fit the company culture,” they’re often encoding preferences for people who look, speak, and think like them—a form of class reproduction disguised as “cultural fit.”

Recruitment practices reinforce this system. In a truly meritocratic world, selection processes would be blind, evaluating only relevant competencies for the role. In practice, “interpersonal skills” are valued—a euphemism for the ability to conform to the dominant culture’s implicit expectations.

Most insidious is how this system perpetuates itself. The beneficiaries of this new aristocracy are trained to see their position as the exclusive result of their merit and effort, conveniently ignoring the structural privileges that facilitated their path. Just as a medieval duke’s son considered his right to lands and titles natural, the executive’s child who attended the best schools and interned at the best companies considers their rapid professional ascension natural.

beyond the corporate fiefdom

If the diagnosis seems bleak, we need not resign ourselves to this state of affairs. Alternatives to corporate feudalism exist—some already underway, others still taking shape.

The Corporate Rebels, for example, have catalogued and disseminated dozens of organizations that have broken with the traditional hierarchical model.8 Buurtzorg in the Netherlands revolutionized the healthcare sector with self-managed teams of nurses. Haier, the Chinese appliance giant, transformed itself into a network of entrepreneurial micro-enterprises. W.L. Gore, manufacturer of Gore-Tex, has operated for decades without traditional hierarchies, using a “sponsorship” system instead of vertical promotions.

Consider also Semco, the famous Brazilian company transformed by Ricardo Semler into a successful experiment in organizational democracy.9 The crucial aspect of these examples is that these companies didn’t sacrifice performance for equality—on the contrary, many thrive precisely because they managed to liberate the creative and productive potential that rigid hierarchies often suffocate.

Even within more traditional structures, there’s room for humanization. Some promising practices include:

- Radical transparency: When everyone has access to the same information, including salaries and decision processes, information-based power is drastically reduced.

- Multidirectional evaluation: Instead of unidirectional evaluations from superior to subordinate, implement systems where everyone evaluates everyone’s work, including leaders’.

- Leadership rotation: Allow different people to assume leadership roles in different projects, based on specific competence, not formal position.

- Collective goal setting: Involve the entire team in defining objectives, instead of top-down hierarchical imposition.

These practices may seem radical in traditional corporate environments, but they represent concrete steps toward moving organizations away from the feudal model.

rethinking what we take for granted

Feudalism hasn’t disappeared—it has metamorphosed. The rigid hierarchical structures, limited social mobility, and ritualization of power from the feudal system find disturbing parallels in modern organizations. Recognizing these historical continuities isn’t mere intellectual exercise, but the first step toward imagining and building alternatives.

As David Graeber wrote: “The ultimate question is how to change from an economy based on artificial scarcity to one based on a collective appreciation of what could be truly valued.” This transformation demands that we question the hierarchies we take as natural or inevitable, recognizing them as social constructs that can—and should—be redesigned.

Part of this problem lies in our obsession with control and predictability.10 Corporate feudalism sustains itself on the illusion that the future can be controlled through carefully orchestrated plans from the upper floors—a fantasy as convenient for modern “lords” as it was for their medieval predecessors. This obsession with prediction and planning often becomes just another way to bureaucratize the future, maintaining power through the pretense of foresight.

It’s not easy, certainly. Those who benefit from the current system are rarely inclined to change it. However, growing unrest suggests that more people are recognizing that current corporate feudalism serves neither individuals nor society. Still, we have evident examples that the logic hasn’t changed in many of our minds, continuing to choose figures for positions of power who increasingly resemble suzerains from epochs and mentalities we thought were overcome.

Perhaps the first step is simply naming what we see. Calling things by their names. When a CEO behaves like an absolute monarch, when a manager demands unquestioning loyalty like a feudal lord, when corporate rituals serve primarily to reinforce hierarchies—we should call these dynamics what they are: anachronistic remnants of a social system we supposedly left behind centuries ago.

Let’s return to wanting to have and be good bosses, yes—but not new feudal lords disguised as enlightened leaders. We should recover the notion of effective management instead of pursuing the nebulous and often empty ideal of “leadership.” We should aspire to organizations that genuinely value merit, collaboration, and human dignity, not just in corporate rhetoric but in their structure and daily practices.

Serious and critical thinking about the future of work, the nature of power in organizations, and the purpose of economic activity is necessary. As a society, we need to ask ourselves: do we want to continue replicating medieval structures dressed in contemporary garb, or are we ready to create work environments truly worthy of the 21st century—and beyond?

The choice, ultimately, doesn’t depend only on the “lords” of the corporate world, who rarely voluntarily abdicate their privileges. It depends above all on all of us who, consciously or unconsciously, perpetuate these structures through our acquiescence. The feudal mentality will only change when we stop playing the game according to the rules of corporate aristocracy—when the “vassals” refuse the role assigned to them and begin to reimagine, collectively, what work can and should be.

What strikes me most about these feudal structures is their resilience across time. They seem to possess an almost organic ability to survive generational changes, technological revolutions, and social upheavals. Each generation believes it will finally break free from these hierarchies, yet somehow they reconstitute themselves, adapting their language and rituals to new contexts while preserving their essential power dynamics. The divine right of kings becomes the invisible hand of the market; the hereditary nobility transforms into the meritocratic elite; the castle walls are replaced by executive floors. The forms change, but the substance endures—a testament to how deeply these patterns are etched into our collective imagination of how human organization “must” function.

Perhaps recognizing this temporal persistence is itself a form of liberation. When we see these structures not as modern innovations but as ancient patterns wearing new clothes, we might finally develop the critical distance necessary to imagine genuinely different ways of working together.

Adapted from the Portuguese essay originally written for Link to Leaders, March 2025. While the examples and contexts may shift across cultures and decades, the fundamental critique remains: our modern workplaces often recreate medieval power structures with disturbing fidelity.

- This type of esoteric language often serves more to obscure than to clarify, functioning as a form of social control within organizations. As I explore in “Beyond ‘Soft Skills’,” the language we use to describe human capabilities reveals deeper assumptions about power and value in organizational life. ↩︎

- This temporal dimension of corporate power connects directly to themes I explore in “The Right to Temporal Dignity,” where I examine how time theft has become normalized in contemporary workplaces. ↩︎

- David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs: A Theory (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018). In “The Utility of Uselessness,” I explore how bureaucratic systems tend to produce structural forms of stupidity that suffocate creativity and independent thinking. ↩︎

- Paul Tabori, The Natural History of Stupidity (New York: Grosset & Dunlap, 1959). See “Emotional Bureaucrats,” where I explore how rules created by bureaucracy are mere “instruments through which human imagination is crushed and shattered,” according to Graeber. ↩︎

- This quote from Graeber appears in Bullshit Jobs: A Theory, where he explicitly connects contemporary workplace hierarchies to feudal structures. ↩︎

- Dave Ulrich, “A New Mandate for Human Resources,” Harvard Business Review 76, no. 1 (January-February 1998): 124–134. In this seminal article, Ulrich proposes that HR should function as strategic partners to organizations, employee advocates, and agents of continuous change, not merely as policy administrators. ↩︎

- See “The Curious Middle,” where I explore how judging that we know what’s best for others is, ultimately, an assassination of their curiosity—both theirs and ours. ↩︎

- For a detailed analysis of these organizational alternatives, see the work of Joost Minnaar and Pim de Morree at Corporate Rebels. ↩︎

- Ricardo Semler, Maverick: The Success Story Behind the World’s Most Unusual Workplace (New York: Warner Books, 1993). Semco grew from $4 million in revenue in 1982 to $212 million in 2003 under Semler’s radical democratic management approach. ↩︎

- As I explore in “Good Enough: Challenging the Tyranny of Excellence,” our pursuit of perfect control often undermines the very flexibility and humanity needed for sustainable success. ↩︎