the treacherous language of capability

What emerges in your mind when someone describes another person as “hard”? You might imagine someone unyielding, resolute, with firm convictions and a direct manner—someone who doesn’t easily reveal vulnerability or emotion. In most professional contexts, these attributes confer advantage, garnering respect and advancement.

Now consider a person described as “soft”—likely someone lacking vigor, easily influenced, indecisive or frivolous. The professional landscape offers few territories where such softness represents an asset rather than a liability.

This isn’t innocent linguistic coincidence. Words carry histories, connotations, and subtle hierarchies of value. The psychoanalytic elephant in our politically correct china shop warrants acknowledgment: these terms’ sexual connotations hint at why hardness receives valorization while softness suffers devaluation—in a world where power’s pendulum still swings toward masculine attributes without serving justice or fostering fulfillment.

Interestingly, even in non-English speaking countries like Portugal, these terms remain untranslated in professional contexts. We don’t say “competências moles” e “competências duras” in everyday business conversations—we use the English “soft skills” and “hard skills.” When I reveal the literal Portuguese translation to audiences, it typically provokes laughter and moments of realization. This linguistic peculiarity reveals how thoroughly we’ve internalized these problematic categories, adopting them wholesale without examining their implications. Business English has colonized professional discourse globally, making us blind to the metaphorical baggage these terms carry across linguistic boundaries.

When we transfer these loaded terms from describing personalities to categorizing professional capabilities, their connotative baggage travels with them. “Hard skills” inherit prestige and concrete value, while “soft skills” absorb connotations of secondary importance, despite countless corporate proclamations to the contrary. The linguistic frame itself undermines what it claims to elevate.

The term “soft skills” reportedly emerged from 1960s United States military training, designating capabilities that didn’t involve machinery operation. Military strategists recognized that these less tangible abilities often determined mission success or failure. From the beginning, these attributes occupied a paradoxical position—simultaneously crucial yet resistant to precise definition, measurable standards, or systematic development.

Decades later, little has fundamentally changed. These nebulous capabilities—rebranded as “interpersonal,” “behavioral,” or “emotional intelligence” skills—still defy clear categorization while being universally acknowledged as essential. The list expands endlessly: charisma, influence, authenticity, listening, sensitivity, wisdom, eloquence, clarity, sincerity, leadership, collaboration, openness, flexibility, vision, presence, humor. One begins to wonder whether these are truly “skills” at all, or something more fundamental—qualities, virtues, or ways of being.

the false dichotomy

The troubling aspect of this binary isn’t merely linguistic but philosophical. It reinforces the Cartesian split between mind and body, between reason and emotion—dualisms that modern neuroscience, psychology, and philosophy have thoroughly dismantled. Our cognitive capacities don’t function in isolation from our emotional intelligence; they’re intricately interwoven systems.

Consider the theater director’s concept of the “it factor”—that ineffable quality that makes certain performers magnetic. The business world, increasingly resembling performance art, similarly mystifies this quality, attributing success to possessing certain “soft skills.” Yet this framing fundamentally misunderstands how human excellence manifests. The great performer, like the exceptional leader, doesn’t simply possess discrete skills that can be isolated and transferred—they embody an integrated way of being.

The boundaries between these supposedly distinct domains dissolve under scrutiny. Reading a financial statement requires technical knowledge (hard) but also pattern recognition and intuitive sense-making (soft). Leading a team discussion demands emotional awareness (soft) alongside systematic problem-solving (hard). 1 The metacognitive ability to reflect on one’s own thought processes—supposedly a quintessential “soft skill”—often proves more challenging than mastering technical knowledge.

This artificial division creates practical absurdities. What advantage comes from analyzing complex data without the ability to communicate its relevance? What benefit lies in eloquent communication without substantive content to convey? Excellence emerges not from accumulating separate skill categories but from their seamless integration within a coherent human being.

The hard/soft dichotomy represents another attempt to render the messy complexity of human capability manageable through oversimplification. Like other binary structures—left/right, liberal/conservative, thinking/feeling—it promises clarity while delivering division. It fragments not just our organizations but our understanding of ourselves, creating internal borders where integration should reign.

the references that define us

To illuminate how profoundly this dichotomy misleads us, I invite you to participate in an exercise I’ve conducted with thousands of participants across diverse contexts over more than a decade. The results remain remarkably consistent across cultures, organizational levels, and professional domains.

Begin by identifying someone who serves as a personal reference point—an individual whose example has significantly shaped your development or understanding of excellence. This might be a family member, teacher, mentor, colleague, or even a public figure whose work has deeply influenced you. Recall specific interactions or observations that left lasting impressions. Now, list five to ten distinctive characteristics that make this person significant in your life—what specific qualities or capabilities do they embody that you find most valuable?

With this list before you, categorize each attribute as either a “skill” (something they know how to do) or a “quality” (a way of being or characteristic of their personhood). When faced with ambiguous cases, make your best determination.

Across hundreds of iterations of this exercise, the pattern emerges with striking consistency: when identifying what we most value in those who influence us, we overwhelmingly name qualities rather than skills. We admire integrity more than technical proficiency, wisdom more than specialized knowledge, compassion more than strategic thinking—though these aren’t mutually exclusive. What impacts us most profoundly is who people are, not merely what they can do.

This observation reveals a profound contradiction. If we predominantly value qualities in those who influence us, why do our educational institutions, professional development programs, and evaluation systems focus almost exclusively on skills? Why does leadership development emphasize competency frameworks rather than the cultivation of character? Why do organizations invest millions in skill development while neglecting the deeper qualities that actually determine how those skills manifest in practice?

The answer likely lies in measurement and predictability. Skills appear more tangible, easier to assess, and less entangled with subjective judgment than qualities. You can evaluate someone’s ability to code, analyze data, or deliver a presentation using standardized metrics. Assessing their integrity, wisdom, or empathy requires entering more ambiguous territory.

Yet this pragmatic explanation reveals a deeper philosophical choice. By prioritizing what we can measure over what we truly value, we’ve created systems that develop precisely what matters least to human flourishing and excellence. We’ve optimized for the quantifiable at the expense of the consequential. 2

the continuity of being and doing

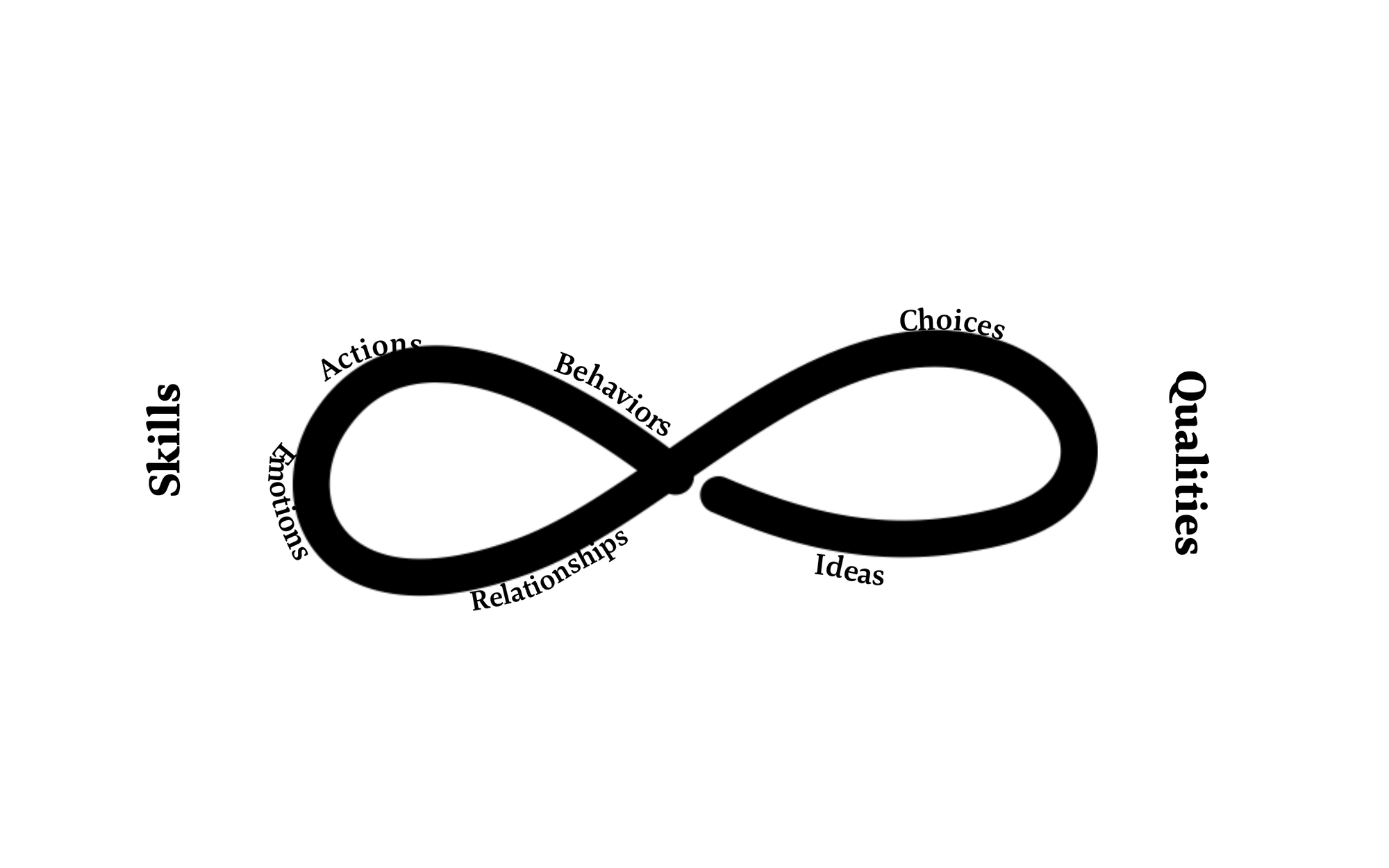

This critique doesn’t suggest an either/or proposition where qualities matter and skills don’t. Rather, it challenges the fundamental separation between them. Qualities and skills exist on a continuum of human capability, each informing and shaping the other.

The common misconception that skills are learned while qualities are innate further complicates matters. This essentialist perspective—that character is fixed while capabilities are malleable—contradicts both ancient wisdom traditions and contemporary developmental psychology. Aristotle’s virtue ethics precisely addressed how qualities of character could be cultivated through practice and habituation. Modern research on neuroplasticity confirms that even fundamental aspects of temperament remain malleable throughout life.

A more nuanced understanding might position skills within the domain of knowing-how-to-do, with their operational dimensions manifesting through productivity and effectiveness. Qualities, by contrast, exist in the realm of knowing-how-to-be, with their ontological dimensions manifesting through ethical and aesthetic expression. Yet these domains constantly interpenetrate—doing shapes being, while being determines how and why we do.

Consider courage, typically categorized as a quality or virtue. One doesn’t simply possess courage as an abstract attribute; it manifests through courageous actions in specific contexts. Through repeatedly acting courageously, one gradually embodies courage more fully. The distinction between having and doing blurs. Similarly, technical mastery—ostensibly a pure skill—cannot be separated from the qualities of patience, persistence, and attention that make its development possible.

This continuity suggests we need a more integrated language for human development—one that recognizes how capabilities, qualities, virtues, and skills form a coherent ecology rather than discrete categories. The ancient Greek concept of arete—excellence of any kind, the fulfillment of purpose—offers one such framework, encompassing both technical mastery and ethical character without artificial separation.

beyond the binary: practical implications of a modern paideia

Abandoning the hard/soft skills dichotomy isn’t merely a philosophical position—it carries profound practical implications for how we approach education, professional development, and organizational design.

For educational institutions, it requires revisiting their fundamental purpose. What if schools and universities returned to their original mission of developing whole human beings—embracing the ancient Greek concept of paideia for our time? 3 This doesn’t mean abandoning technical education, but rather embedding it within a broader framework of human development. Writing code becomes not merely a technical act but an ethical one, shaped by questions of purpose, impact, and responsibility.

It also reflects broader societal discomfort with moral evaluation, a symptom of our eroding collective moral compass. Science and business often retreat from explicit value judgments, seeking a neutrality that ultimately proves illusory. Every organizational decision—from who to hire to what to prioritize—already embodies moral choices, whether acknowledged or not. We face not whether to make value judgments but whether to make them consciously and deliberately.

I advocate abandoning the illusion of neutrality altogether if we want meaningful change. Consider a simple mathematical metaphor: if an entity (“1”) seeks transformation and we add a neutral element (“0”), nothing happens. True change requires adding an unknown variable (“X”)—something neither the helper nor the helped can fully predict but must discover together. This unknown space is essential for producing rich, unpredictable, and meaningful transformation that change agents can legitimately claim responsibility for. 4

toward an integrated human development

The encouraging news is that some organizations are already moving in this direction. More companies are taking explicit moral positions on issues from climate change to social justice, recognizing that neutrality itself represents a moral stance. This external moral positioning creates space for more integrated approaches to internal development—connecting technical capabilities with ethical purpose and human qualities.

For this evolution to succeed, it must extend beyond corporate environments. Educational institutions must reclaim their role in developing not just competent professionals but good people. Families need space to nurture human development without exhaustion from professional demands. Communities must support both by fostering environments where qualities of character receive as much attention as technical and economic achievement.

This isn’t a call for abandoning skill development or technical education. It’s an invitation to recognize that skills divorced from qualities become empty or even dangerous—technical capability without ethical guidance. Simultaneously, qualities without skills lack the means for effective expression in the world.

The path forward begins with language—abandoning the misleading hard/soft dichotomy in favor of more integrated frameworks. It continues through systems—redesigning educational and organizational approaches to develop whole human beings rather than skill repositories. It culminates in a renewed understanding of excellence as the harmonious integration of doing and being, of technical capability and human quality.

What we ultimately seek isn’t a workforce with the right mix of hard and soft skills, but communities of whole human beings bringing their full capabilities to address our shared challenges. The challenges we face—from climate change to technological disruption to social division—demand nothing less than this integration. They cannot be solved through technical expertise alone, nor through interpersonal capabilities in isolation. They require the full spectrum of human excellence.

The ancient Greeks had a word for this integration: kalokagathia—the beautiful and the good united, where excellence of character and capability become inseparable. In rediscovering this unified vision, we might find our way beyond the artificial divisions that fragment not just our organizations but our very selves.

We’re not asking whether you need hard skills or soft skills. We’re asking who you are becoming through what you do—and what that becoming makes possible in a world desperately needing integrated excellence.

-

This integration of technical and interpersonal capabilities mirrors what I explored in “The Conversations of Lovers and Teams,” where the most effective conversations blend structured problem-solving with emotional attunement—neither functioning optimally without the other. ↩︎

-

This obsession with measurement mirrors what I explored in “Good Enough: Challenging the Tyranny of Excellence,” where our relentless pursuit of quantifiable excellence often undermines the sustainable, humane development that actually produces lasting value. ↩︎

-

Paideia represents the cultivation of the complete human being—intellectually, morally, physically, and spiritually. Unlike our compartmentalized modern education, it wasn’t about producing specialists but developing individuals who could think deeply, act ethically, and pursue excellence in all aspects of life. ↩︎

-

This perspective on change connects with ideas in “The Utility of Uselessness,” where I explored how seemingly non-instrumental activities often produce profound transformations precisely because they aren’t constrained by predetermined outcomes. The “useless” space of exploration without guaranteed results creates the conditions for genuine discovery. ↩︎