writing from beyond utility

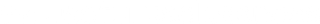

It began with death. Or rather, with someone writing after death. Machado de Assis’s Memórias Póstumas de Brás Cubas (The Posthumous Memoirs of Brás Cubas) in Tinta da China’s edition. Here was uselessness itself: a dead man writing his autobiography, beginning from the grave with sarcasm, humor, and some bitterness about the life he left behind.

The book was written, as we know from the beginning, “with the pen of jest and the ink of melancholy.” What could be more useless than a dead author’s reflections? Yet this uselessness created one of Portuguese-language literature’s masterpieces. Brás Cubas, freed from life’s obligations, can finally tell the truth about the living. His uselessness becomes his authority.

Machado’s premise is liberating. Only in death can the narrator achieve the clarity to dissect life’s pretensions. The dead have no objectives to meet, no personal brand to maintain, no network to cultivate. From this position of complete uselessness comes literature of enduring use.

the collector’s paradox

This meditation on the useless dead made me receptive to Fredrik Sjöberg’s A Arte de Coleccionar Moscas (The Art of Collecting Flies), published this April by Livros Zigurate. The book’s intensity of curiosity ignited something in me. Here was another kind of death—the pinned specimens of an entomologist’s collection—transformed into a meditation on life.

The book is, as its subtitle suggests, halfway between memoir, natural history lesson, and philosophical reflection: a surprising meditation on happiness that is enchanting, contemplative, and full of humor. Sjöberg speaks of slowness, the poetry of waiting, the desire to collect that compensates for the chaos of existence. Here was an entomologist who had discovered 202 species of hoverfly on his tiny Swedish island—fifteen square kilometers of apparent nothing yielding endless fascination.

The book opens with Guatemalan writer Augusto Monterroso’s epigraph: “There are three themes: love, death, and flies.” Sjöberg takes this literally, using his seemingly useless obsession with these insects as a lens through which to observe the world with different eyes. What struck me wasn’t just the beauty of dedicating one’s life to something so apparently pointless, but how this dedication showed things I couldn’t see while rushing toward utility. As Sjöberg told Público in April, “collecting insects is a kind of yoga”—a way to exercise slowness and concentration so intense that one forgets oneself. In our age of productivity worship, such forgetting becomes resistance.

Ignorantly, I always questioned the utility of flies, as a way to mask my hatred for the animal. Now, after this book, I began to admire and, even possibly, love these irritating flying insects.

the velocity of forgetting

The book mentions writers like Chatwin, Kundera, and D.H. Lawrence, all fascinated by collecting. This reference to Kundera sent me searching, and I found myself ordering A Lentidão (Slowness) from Dom Quixote’s 2022 edition. I picked it up at a bookstore during a transition between Alentejo and Praia Grande.

Kundera’s novella interweaves an 18th-century libertine romance with a contemporary journey to a French château transformed into a hotel, where an entomology conference is taking place. The synchronicity wasn’t lost on me. Entomologists appearing in both books, as if the universe were making a point about attention to the minute and seemingly insignificant.

But beneath this libertine fantasy lies a profound meditation on modernity’s effects on our perception of the world; on the secret link between slowness and memory; on the connection between our contemporary desire to forget and how we surrender ourselves to the demon of speed. Kundera argues that speed is conducive to forgetting: when we have a bad thought, we accelerate our pace. Slowness, on the other hand, is faithful to memory: we slow down when recalling something beautiful.

In our era of instant everything, have we chosen speed precisely because we want to forget? And what are we so desperate to leave behind?

the cost of explanation

Then came the book that initially seemed out of place in this meditation: Rebecca Solnit’s Men Explain Things to Me (Granta Books’ August 2023 edition). “You should read this,” Inês, my wife, said, handing me the book. She was right. All men should read this, first, and women too, though for different reasons.

The essay that inspired the term ‘mansplaining’ describes the time when, at a party, a man explained to Solnit the argument of her own book. At first glance, this might seem unrelated to flies and slowness and posthumous memoirs. But I realized it was the most important “useless” thing I’d read. Useless in the sense that it told me things that, as a man, I thought I already knew. But, precisely because of that confidence, some of those things may very well have been transparent to me. It made me ask questions of women close to me that I’d never thought to ask. It showed my role not just in avoiding harm but in the active work of equality.

As Solnit writes, mansplaining is “the intersection between overconfidence and cluelessness where some portion of that gender gets stuck.” It’s about the silencing of voices, the assumption that some perspectives matter more than others. In essence, it’s about who gets to determine what’s useful and what’s not.

Reading Solnit made me realize how often we dismiss as “useless” anything that doesn’t serve our immediate purposes or confirm our existing beliefs. But sometimes, shutting up and listening—to flies, to the dead, to the living who’ve been told their contributions don’t matter—can be of great use.

the post-everything world

I haven’t yet finished Stuart Jeffries’s Everything, All the Time, Everywhere: How We Became Postmodern (Portuguese edition from Livros Zigurate), but it’s already reshaping how I understand the others. Jeffries argues that postmodernism, with its rejection of grand narratives and embrace of surface and play, was “the fig leaf for a rapacious new kind of capitalism.”

He traces a history from the early 1970s through David Bowie, the iPod, Frederic Jameson, Madonna, Jeff Koons, and the demolition of Pruitt-Igoe—a riotous gallery of how we learned to stop worrying and love the meaningless. In our rush to declare everything meaningless, we’ve missed the meaning in the apparently meaningless. The flies. The slowness. The voice from beyond the grave. The woman trying to finish her sentence.

This connects to something I’ve been exploring in my own work—what I call the post-depth era, where we’ve abandoned profundity not because we’ve transcended it but because we’ve forgotten how to dive. We splash in the shallows, mistaking activity for meaning, motion for progress. The manuscript I’m finishing—an anthology of essays on this subject, including revised versions of pieces published here—argues that our fear of depth isn’t philosophical sophistication but existential cowardice. We’ve confused the difficult work of meaning-making with the easy cynicism of meaning-denial.

the thread of connection

These five books, picked up for no conscious reason or logic, read across a summer break, somehow speak to each other. Each questions what our culture dismisses as worthless: the patient observation of insects, the slowness that holds memory, the dead’s perspective on the living, the voices we don’t let finish, the view of how we arrived at this strange moment.

Together they suggest something about the usefully useless—those activities and obsessions that optimize nothing while keeping something essential alive.

what remains

As I write this, summer has almost ended but these books continue their conversation in my mind. Sjöberg is still counting flies on his island. Kundera’s château still hosts its strange confluence of centuries. Brás Cubas still mocks from beyond. Solnit still insists on finishing her sentences. And Jeffries still maps our strange postmodern moment where everything is possible and nothing matters.

As Sjöberg believes, “deep down, we’re all fly collectors, even if we don’t know it.” We all have our useless obsessions, our slow observations, our voices from beyond productivity’s grave.

In a world that monetizes attention, quantifies relationships, and optimizes experience, what does it mean to spend a summer reading about flies? Or to write from beyond utility’s reach. Or simply to slow down enough to remember why we once thought speeding up would save us.

The books sit on my shelves now, except for one that is yet to be finished. They remind me that not everything needs to serve a purpose, and that, sometimes, the best things serve no purpose at all. That can be their precise point.

Early backer discount. There's a one-time 60% discount on your first payment during of The Useful Uselessness.Thats about 16€ the first year.

This is a reader supported publication. If you enjoy the content, please consider a paid subscription or a donation. Also, if you thought of someone while reading the content, don’t hesitate to share it with them.